10 minutes reading time

Floating like 300 tons

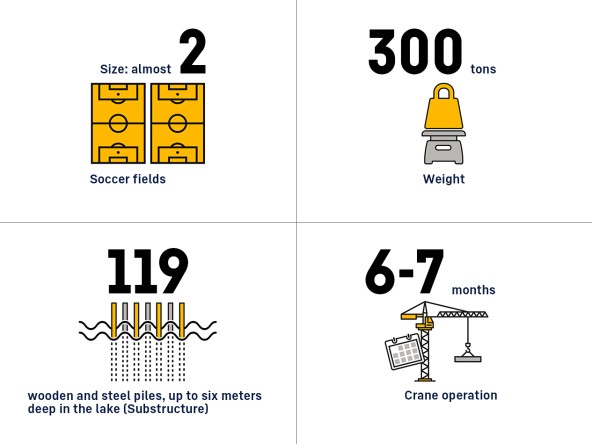

A giant sheet of paper floats above Lake Constance – a perfect illusion of weightlessness, and yet the timber, polystyrene and steel structure weighs around 300 tons. This is the set for a production of Puccini’s opera “Madame Butterfly”, which will premiere on the floating stage of Bregenz on July 20, 2022. But why is a sheet of paper the setting for this tragic love story? What gives all this heavyweight technology this illusion of lightness? And what does one Liebherr crane have to do with any of it?

Rising suspense as the stage is set

The premiere is getting closer by the day. Wolfgang Urstadt, technical director of the Bregenz Festival, is slightly nervous as he gazes toward Lake Constance, where the final lifting operations on the floating stage are taking place. Only a handful of the 117 individual parts that will later form the stage are still missing. Urstadt, who trained as a carpenter and stage manager, has been tackling a monumental undertaking over the past weeks and months: The world’s largest floating stage is slowly but surely getting ready for the next opera season. And expectations are high – after all, the festival is well known for its spectacular backdrops and colossal stage sets. Urstadt has been planning, organizing and coordinating the work for the last three years. Now there is nothing left for him to do but watch as one by one the last sections are attached to the stage, which is more than 20 metres high. Liebherr was brought on board for the lifting work. The 150 EC-B 8 Litronic flat-top crane ensured smooth operations where scenery parts weighing several tonnes had to be transported with maximum precision.

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).The shattered soul of Madame Butterfly

Today, “Madame Butterfly” is one of the most frequently performed operas in the world. Yet when it premiered at La Scala in Milan in 1904, it was a resounding flop. Puccini revised his creation and managed to win over the audience in Brescia in the same year. The tragedy revolves around the Japanese geisha Cio-Cio-San, or Butterfly, who falls in love with Pinkerton, a lieutenant in the US navy. He marries her according to Japanese custom before sailing back to his homeland. Butterfly gives birth to his child shortly after and waits three years for her beloved husband to return. It is not until he returns with his American wife in tow that she realizes he never took their union seriously. She hands the child over to him and takes her own life.

Journey of an artwork: from imagination to reality

The idea for the stage design is the brainchild of Canadian designer Michael Levine, who has been designing sets for the world’s most renowned stages for almost forty years. This is his first time in Bregenz. He began by designing a model and then digitizing it. His vision: a large, ultra-thin sheet of parchment floating on Lake Constance, looking as if it had been heedlessly crumpled and tossed into the water. One side of the sheet has a slight upward curve over the surface of the lake. An ink painting of a Japanese landscape can be seen on the bright white surface. It is unprotected and at the mercy of the waves. Nestled against it on the right is a paper ship, painted with elements of the American flag. “Fragile and ornate,” is how Artistic Director Elisabeth Sobotka describes the set. The sheet of paper, with its fragility and delicacy, symbolizes the main character in this tragic opera.

The enormous technical challenge facing Urstadt was to turn Levine's vision into reality by placing a floating “sheet of paper” more than 1,340 square metres in size on the lake surface. Using folds and curves to create an impression of lightness – while building the entire structure in such a way that it will hold up in the water in all weather and be safe to walk on.

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).Art under construction or an artistic construction site?

“For me, the essential work has already been done,” says Urstadt as the penultimate piece of scenery inches closer to the workers on the stage. The technicians, secured with safety harnesses at around 23 metres height and moving around the set at a fast pace, start attaching the piece of scenery as soon as the crane has come to a halt. “We spend about three to four years on average working on a project. We are well within schedule. Originally, four or five extra days had been planned for lifting the individual sections of the sheet of paper. Apparently, we don’t need them anymore,” says Urstadt with a smile, while on the shore of Lake Constance, other members of the team are busy preparing the last component for the next lift.

The individual polystyrene blocks, which were placed in their positions on the stage one by one, were manufactured in an assembly hall in the neighboring town. They are all different sizes and were shipped by special transport to the shore of Lake Constance, where they were transformed into a walkable sculpture in the water, about 23 metres high and 33 metres wide.

“The crane fits the pieces together like a puzzle,” says Urstadt, commenting on the action. “Here on Lake Constance, we can of course achieve vastly different dimensions than in a theater. The components are all quite large and building the set is heavily dependent on the weather – in fact, it’s just like being on a construction site – only in the water. We needed divers for many of the tasks, such as the erection of the crane itself. The crane’s undercarriage was pre-assembled and partially ballasted on land because it was impossible to hammer in the bolts underwater.”

Many years ago, we would construct the set without using a crane. But with the way expectations have grown and how we build today, that wouldn’t be possible now at all.

The workers on the shore watch the crane as the boom moves farther and farther away from the stage. As soon as the crane hook is back in position, they start attaching the last piece of scenery. “The 150 EC-B used here has a load capacity of eight tons. This meant that it was possible to construct the stage out of relatively heavy individual parts. If we had used a lower capacity crane, we would have had to make the set from many more individual parts,” explains Urstadt. It is also important to use a sensitive crane for the work, which is carried out in front of a perfect Alpine backdrop.

A jigsaw puzzle for crane operators

The sensitivity of the control system is particularly appreciated by the crane operator. Lifting sections onto the floating stage is a precision job that requires experience. Roland Bühler, who goes by the name of Chappie, has plenty of this. He has had one of the best views of the floating stage for 20 years now. Madame Butterfly is his tenth opera set. Despite this, even he finds the task challenging: “Fitting the 117 elements seamlessly into one another was high-grade precision work. But it went very smoothly thanks to the crane’s control system. It does exactly what I want,” says Chappie, who has an impressive total of 12,000 crane operating hours under his belt.

The floating stage technicians and the crane operator are a well-rehearsed team. Half of the stage set is underwater, where Chappie can’t see anything. In some situations, this meant that he was like a pilot flying blind – wholly reliant on the ground crew’s instructions. What felt like a 300-tonne weight fell from his shoulders when the last part of the set was firmly installed and the stage crew radioed the signal for lunch. The basic framework of the stage was in place. “One of the things I love most about working up here is the variety. You start off with the steel construction, then move on to stage construction, and every two years something entirely different comes along again. One thing’s for sure: I never get bored here,” laughs Chappie.

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).

Profile of the floating stage 2022/2023

Wolfgang Urstadt ticks off one more item on the project plan: The stage is up. But the work goes on. His next challenge is to make the composite surface look like a unified whole. “We had to plan everything, starting from the materials, to ensure a smooth, even surface,” says Urstadt. For this purpose, the entire scenery sheet had to be treated with facade plaster and painted to match.

When the performers finally took to the stage, Urstadt took on the role of the observer. The suspense will remain until all 26 performances, during which the stage set and all the technology must operate without a hitch, are over. “There are 400 to 500 people involved in the production. Everyone is important, every nut, bolt and screw. And of course, there is always plenty of opportunity for something to go wrong,” says Urstadt. But even if it does: The roughly 250,000 people who attend the Bregenz Festival generally don’t even notice.

And while the audience is enjoying the perfect illusion of 300 tonnes of weightlessness at every performance, Urstadt is already busy elsewhere. Because after the game is before the game in the arts as well: Planning for the 2024 production has long been underway, with other, equally spectacular challenges.

The lake stage over the years

Madame Butterfly in Bregenz, Austria

Enrique Mazzola, Yi-Chen Lin

Andreas Homoki

Lukáš Vasilek / Benjamin Lack

Prague Philharmonic Choir / Bregenzer Festspielchor

Wiener Symphoniker

Celine Byrne, Elena Guseva, Barno Ismatullaeva

Edgaras Montvidas, Otar Jorjikia, Łukasz Załęski