Innovative without blinkers

We live in transformative times, characterised by climate change, the shift away from fossil fuels and rapidly advancing digitisation. The innovations and drive systems that will lead into the future are a matter of concern for politicians, scientists and researchers – and especially for the manufacturers of construction machines. Jürgen Appel, head of technology coordination at Liebherr-International AG, on a technology-open approach, bundled competences and the not-always-easy search for the right solutions for different applications.

Mr Appel, we are living in unusual times, which today are often described as VUCA: Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity. How do you experience this at Liebherr and what challenges does this pose for technological development?

Jürgen Appel: VUCA is impacting many areas of technological development. Climate change, digitisation and the globalisation of production and supply chains are defining the guidelines. Under these changed conditions, Liebherr’s task is to modernise the drives of its construction machines in such a way that they produce significantly less CO2 – across the entire product life cycle. At the same time, we have to keep pace with ever new legislative and regulatory requirements when it comes to selecting the right drives for the most diverse application scenarios of our machines.

What does this mean for the overall view of technology?

Jürgen Appel: We definitely have to define them much more broadly than in the past. Just think of the digitisation of machines and their processes. Today, construction machines no longer only perform physical work, but also produce a large amount of data that makes life easier for users, but can also be used for further technological development and process optimisation. In addition, the data obtained also pave the way for completely new business models for our customers. All this shows that the development of construction machines and technologies today requires far more than just conventional engineering. It is more about bundling different competences and achieving a new level of quality in terms of development.

What does that mean, exactly?

Jürgen Appel: Whereas in the past the focus was clearly on the product during development, today it is also a question of including environmental aspects and thinking about existing possibilities and impossibilities from the outset. It makes no sense, for example, to develop alternative drives based on renewable energies without taking into account their availability and the development of a corresponding infrastructure. In the end, our machines should also actually be able to work for our customers.

Why is attention only being shifted to alternative drives now? The fact that they would be in demand against the backdrop of climate change and the finite nature of fossil fuels is not an entirely new or surprising realisation.

Jürgen Appel: This has mainly to do with the fact that fuel, above all diesel, was available everywhere as a means of propulsion and that engine technology was continuously developed with a view to reducing pollutants. Nevertheless, Liebherr has been working on alternative drive concepts for a long time and has various machines in its portfolio that are also powered purely from the mains. In the meantime, the political and legislative assessments, exacerbated by the supply bottlenecks in the wake of the war in Ukraine, have changed fundamentally. The end of fossil fuels is a done deal. In order to quickly arrive at independent and feasible alternatives in this scenario, we at Liebherr see this as confirmation of our efforts to continue not simply relying on just one factor, such as electric mobility, but looking at several different solutions in parallel.

How does Liebherr go about this?

Jürgen Appel: Looking at sustainable CO2-free or at least CO2-neutral drives, there will not be a single, one-size-fits-all concept for every application covered by construction machines. A compact wheel loader in horticulture simply has different requirements than a 100-tonne crawler excavator for mining at 5,000 metres in the Andes. In other words, a whole host of very different competences are required to develop drive concepts.

Where do these competencies come from?

Jürgen Appel: At Liebherr, we are very broadly positioned across our various product segments. The Liebherr family wanted to bundle this practical knowledge accumulated over many decades, create synergies and enable springboard innovations, when three years ago it brought together various future and development projects of its product segments in specially created, centrally coordinated groups of experts in its newly created Corporate Technology central unit.

How does such cooperation between experts from the different product segments work? Do they enjoy sharing and discussing their ideas?

Jürgen Appel: There are no reservations at all. On the contrary. We were soon able to identify experts, who now meet regularly across all segments and exchange views on the upcoming future topics in a very intensive and motivated manner. It is in the nature of things that the individual product segments arrive at various solutions for different customers on similar topics, such as new digitally driven business models. The earthmoving product segment sets its priorities differently to our crane experts. However, if there are overarching issues, such as the equipment and use of battery-electric drives, it makes sense to bring together the individual competences available to us in each case. We have created our own competence centres at Liebherr for this purpose, such as the one in Biberach for batteries or the “Liebherr Digital Development Center” in Ulm.

And what do the product segments have to say about this form of centralisation?

Jürgen Appel: They are aware of the advantages that result from this strategy for the company as a whole, but also directly for themselves. After all, the product segments are and will remain responsible for their respective products at Liebherr. They simply know the needs of their customers and target markets best. Thus, the bundling of cross-divisional competences is not at all about centrally prescribing which products are to be manufactured and how they should look. Rather, the competence centres start where a product segment reaches the limits of its expertise and wants to open up new possibilities for action in dialogue with others who are already further advanced at this point.

Can you give an example of this?

Jürgen Appel: There are many examples on the technological side, such as batteries and charging infrastructure or in the broad field of hydrogen drives. The transfer of expertise at Liebherr has recently been particularly intensive and extremely successful on the regulatory side. Brexit had been hanging over the economic partners as a sword of Damocles since the 2016 vote, but when the time came on 1 January 2021, there was great uncertainty on both sides as to which rules would apply to whom and what would have to be observed administratively in the exchange of goods and commodities.

How were you able to meet this challenge at Liebherr?

Jürgen Appel: All of our sites that supply equipment or components to the UK were faced with the question of which administrative and customs requirements had to be fulfilled overnight for the movement of goods when Brexit came into force. Because there was a lot of uncertainty and confusion on both sides of the border, we very soon set up an expert group. Together with lawyers, customs experts and logistics specialists, the expert group developed a company-wide Brexit guide within a short period of time, which now applies to all our sites. This means that not every single Liebherr subsidiary doing business with the UK has to clarify each time with experts what information has to be on the type plate according to the new regulations or what the obligatory “UK Declaration of Conformity” has to contain. This highly practical service has been very well received within the company.

Many roads lead to Rome. This is both confirmation and encouragement for the technology-open approach that Liebherr has chosen.

How does such a concerted approach affect the development of alternative drives?

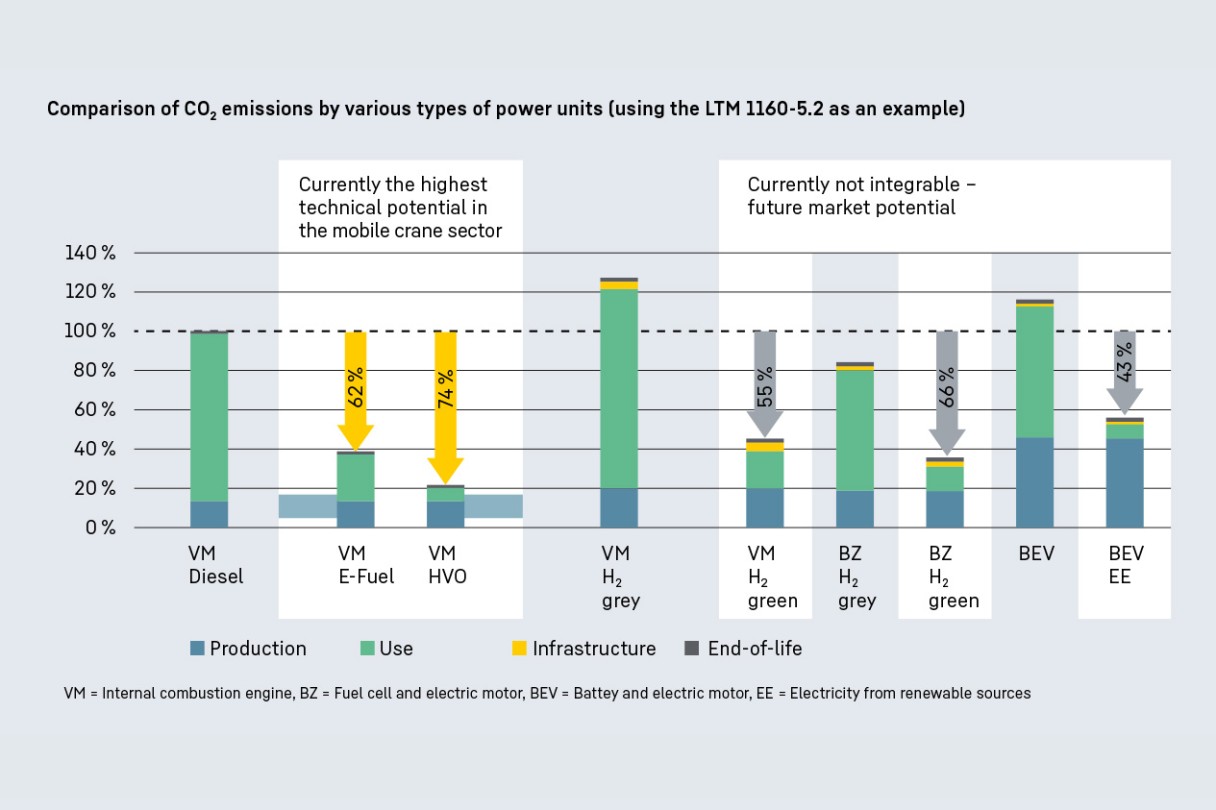

Jürgen Appel: Before evaluating alternative drives, we first wanted to clarify the overall carbon footprint of construction machines. To this end, in collaboration with the economic advisor Frontier Economics we recently conducted a comprehensive life cycle analysis of the greenhouse gas emissions generated by typical construction machines. One and the same machine was equipped with different drive solutions and examined. This results showed that there is no superior, standard solution for selecting the right climate-neutral drives to be installed in construction machines. Again: Many roads lead to Rome. This is both confirmation and encouragement for the technology-open approach that Liebherr has chosen, in order to reduce emissions as efficiently as possible, depending on the machine and application, in an absolutely tailored and functional way.

What does this mean for Liebherr’s culture of innovation?

Jürgen Appel: Real innovation is not simply a box-ticking exercise. The study provides impressive evidence of this fact. At Liebherr, we have always been committed to open-ended research and development with a clear focus on the performance and cost-effectiveness of our machines. If necessary, we also involve partners who, for example as start-ups, are a little more agile and quicker than a large, globally operating group and can thus often contribute exciting impulses that lead to new solutions.

After all the experiences we have had so far: What do you personally think about a technology-open approach?

Jürgen Appel: The Frontier Economics study proves how little sense it makes to align engineering with political or perhaps even ideological guidelines. Innovations must serve the user and not the other way round. That’s Liebherr-like. We will only achieve the targeted and necessary CO2 reductions with a holistic view of the entire life cycle of a machine. This is not possible with technological blinkers. Instead, we need to focus on the fact that sustainable and climate-relevant innovations must ultimately be technologically representable in such a way that the customer can also work with them. I find it incredibly exciting and rewarding for everyone involved that there is not only one way to reach the goal.