Reaching into the depths

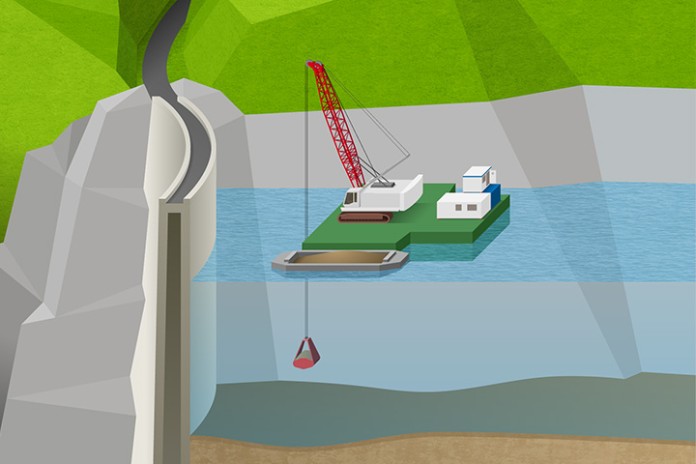

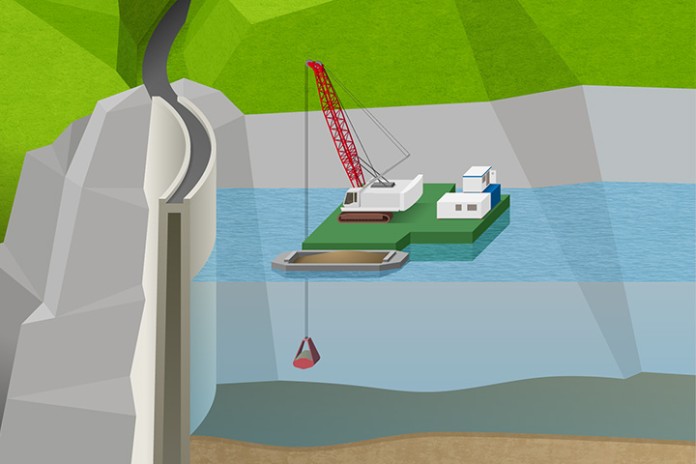

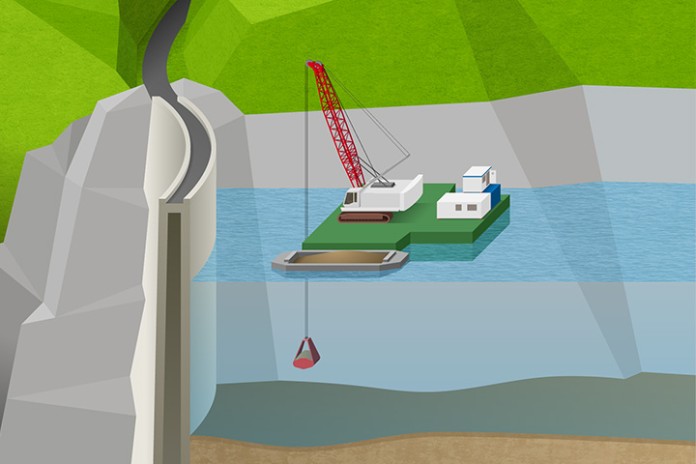

A huge cloud of mud spreads out in the water in front of the high dam wall of Lago di Luzzone in the Swiss canton of Ticino. With a gurgle, the bright red clamshell grab, which weighs over a tonne, rises out of the water, sending a fountain of water soaring up several metres high. The powerful metal fist, which Yann Blouet, one of two crane operators, controls almost playfully with a kind of joystick, holds ten cubic metres of mud and debris. He navigates it to the loading area of the lighter, a ponderous transport vessel, which has drawn up right alongside the crane. The grab opens and releases its wet load. "I dredge sediment out about twelve times an hour," says Blouet. "The handling volume is huge."

By 2018, the duty cycle crawler crane supplied to the French construction company S.E. Levage will have dredged as much as 125,000 cubic metres of material out of the reservoir. The reason for doing this: The power plant in nearby Olivone that is connected to the reservoir does not obtain sufficient water pressure if debris and sediment block up the filter grid in front of the outlet. As this cannot be completely prevented in this high-alpine environment, the power plant has been shut down in the summer months for three consecutive years. The Liebherr HS 8130 HD duty cycle crawler crane, which is firmly anchored on a barge close to the dam wall, can then begin its work. The crane brings considerable power to the task: the engine has a power rating of 505 kW, the crane's lifting capacity is 130 tonnes and its tractive power is 2 x 350 kN. Depending on the depth at which it is working, the XXL machine at the reservoir in Switzerland can handle up to 130 cubic metres an hour.

The challenge here is the depth from which the sediment has to be dredged up. We go down as far as 200 metres to the bottom of the lake.

Fascination of the depths

Yann Blouet, who with his goatee and moustache looks a little like his rock idol Frank Zappa, is fascinated by his workplace at 1,600 metres above sea level: "The challenge here is the depth from which the sediment has to be dredged up. We go down as far as 200 metres to the bottom of the lake," he explains.

Up here, surprises are part and parcel of a crane operator's job description: for example, the work can be hampered by wind, heavy rain and rockfalls or a sudden deterioration in the weather. Blouet sometimes also dredges up a surprising or unpleasant load, such as a dead animal – a sheep, a deer or a chamois which has slipped off the smooth rocks into the lake and drowned. Often there are also really large trees or rocks that have to be removed from the underwater grid.

"The grab takes several minutes to get to its deep underwater dredging point," says Blouet. Nothing can be seen down there. "I feel it with the grab." Blouet's hands clasp the joystick in the cockpit as he glances at the monitor with the GPS display that uses coloured bars to show him the depth at which the grabber is located. Blouet operates the control lever at the current depth of 150 metres: once again, he is moving a little closer to his target of having completely cleared the grid to a depth of 200 metres.

Investing a lot of power to obtain more energy

HS 8130 HD duty cycle crawler crane

Find out more

Special assignment: dredging

Find out more

Energy source: hydropower

Find out more

The power plant's output

Find out more

Logistics

Precision work

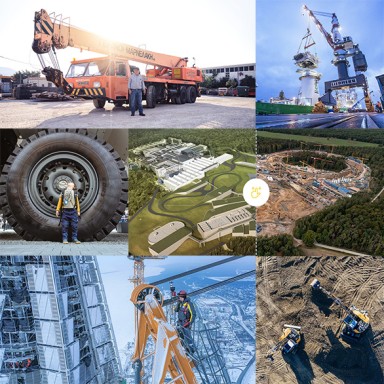

How do you get a crane through the eye of a needle? Transporting the duty cycle crawler crane to its operating site in the Ticino Alps was an adventure and a technical masterpiece in terms of logistics.

The duty cycle crawler crane is flexible and can be deployed almost anywhere. However, the construction site at Lago di Luzzone is far from being an ordinary location. The reservoir lies at 1,600 metres above sea level at the upper end of the Blenio valley. The route to the dam wall follows a narrow road winding uphill. It poses a genuine challenge in terms of transport logistics and calls for precision planning, literally to the millimetre.

How can the exceptionally long articulated lorry manage the hairpin bends? How can the dismantled crane be driven up the valley road out of Val Carassino and manoeuvred through two tunnels? One is damp and cold, the other long and dark. "On top of this, there is the threat of falling rocks due to heavy rain," says Paul Hotz from the logistics company JMS-RISI, outlining the risks.

Prior to transportation, the logisticians had prepared templates which they used for measuring the narrow passages in the tunnels and for planning how to negotiate the hairpin bends on mountain roads with 300-metre drops down spruce-covered slopes, and manage the journey over the dam wall, which is just under 225 metres high. "Everything went smoothly," says Hotz, evidently relieved to have completed the challenging delivery.

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Privacy Settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).

Out on the lake, Yann Blouet is not alone

Every morning at six o'clock, the crane operator and a boatman go out to the barge in a small boat. Blouet checks the crane's oil gauge and the measurement level and lets the engine warm up for a few minutes. In the cab, he has put on "some quiet background music" which allows him to forget that he is alone in the cab in this alpine mountain world.

The day begins. The boatman moors the lighter against the barge, receives the load from the dredger's grab once, twice, waits until the lighter is full and then takes the load to the other end of the lake. It will be half an hour until he returns. In the meantime, Blouet fills the lighter on the other side of the barge.

A fascination with technology

Dredging in the lake is not possible in the winter. Yann Blouet then has time to call in at the Liebherr plant in Nenzing. Even after almost twenty years of experience in the job, he is still enthusiastic about the processes used there in the production of the various crawler cranes, duty cycle crawler cranes and piling and drilling rigs. "I find anything to do with technology interesting," says Blouet. In the plant, the sparks fly up into the dark air in the production shop. The building is as tall as an aircraft hangar. A fitter cuts metal sheets for the vehicles. The "boom" and the "needle", the two arms of a duty cycle crawler crane, lie on the bare floor as if in a state of slumber. Blouet talks shop with the workers, showing interest in every detail, however small. This goes down well at the plant. "After all, quality is important to all of us," says Blouet. This applies as much to the design, production and processing as it does to ensuring absolutely safe and reliable use in the often harsh conditions of day-to-day work.

I enjoy working in this environment with its unparalleled combination of technology and nature.

Back to Lago di Luzzone. Blouet is dredging close to the reservoir dam. But the crane operator is not entirely happy with what he is lifting out. The monitor shows a distance of twenty metres from the outflow grid. Blouet reaches for the walkie-talkie and calls to the barge operator behind him: "Move closer in!" The barge moves forward slowly. Only another ten metres or so to the wall. Blouet lets the grab shoot down. Blouet's dredger, with its 32-metre-long boom, is now almost dwarfed by the more-than-200-metre-high concrete wall looming over it.