10 minutes reading time

Beyond the horizon

Ships are a very special means of transportation. Since time immemorial, people have boarded ships to brave the elements and travel to distant continents. The value of a ship, however, is not limited to the high seas. Scrapping and recycling can open up unexpected new horizons – both for the circular economy and for the environment.

A stormy night

“Mayday Mayday Mayday - this is MV Kaami...” It was a dark and stormy night in March when the radio operator sent out a distress call. The Norwegian freighter had run aground on the north-west coast of Scotland on its journey to Sweden from Ireland. For a seafarer, this is one of the worst disasters imaginable. The eight crew members had to be airlifted to safety by helicopter. But there was no saving the ship, which had been originally launched in 1994. Experts soon confirmed that the damage caused by the accident was irreparable.

But what do you do with a ship written off as a “constructive loss” by the insurance company? Nowadays, simply scuttling it is out of the question. But towing the wrecked vessel to a ship graveyard and leaving it there to slowly decay, as is still the case today with well over 100 larger fishing vessels in the Bay of Nouadhibou on the Mauritania coast (West Africa), harbours incalculable environmental risks due to oil losses and the gradual release of pollutants.

The alternative is to have the ship dismantled properly in a ship-breaking yard. These yards could be found all over the world until well into the 20th century. Over time, this business migrated from Europe to Asia – especially India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and China – because of the availability of cheaper labour and less stringent environmental laws. This brings its own problems, however. Catastrophic working conditions in many of these ship-breaking yards and the extreme hazards they pose for both people and the environment have often put this type of scrapping in a very critical light.

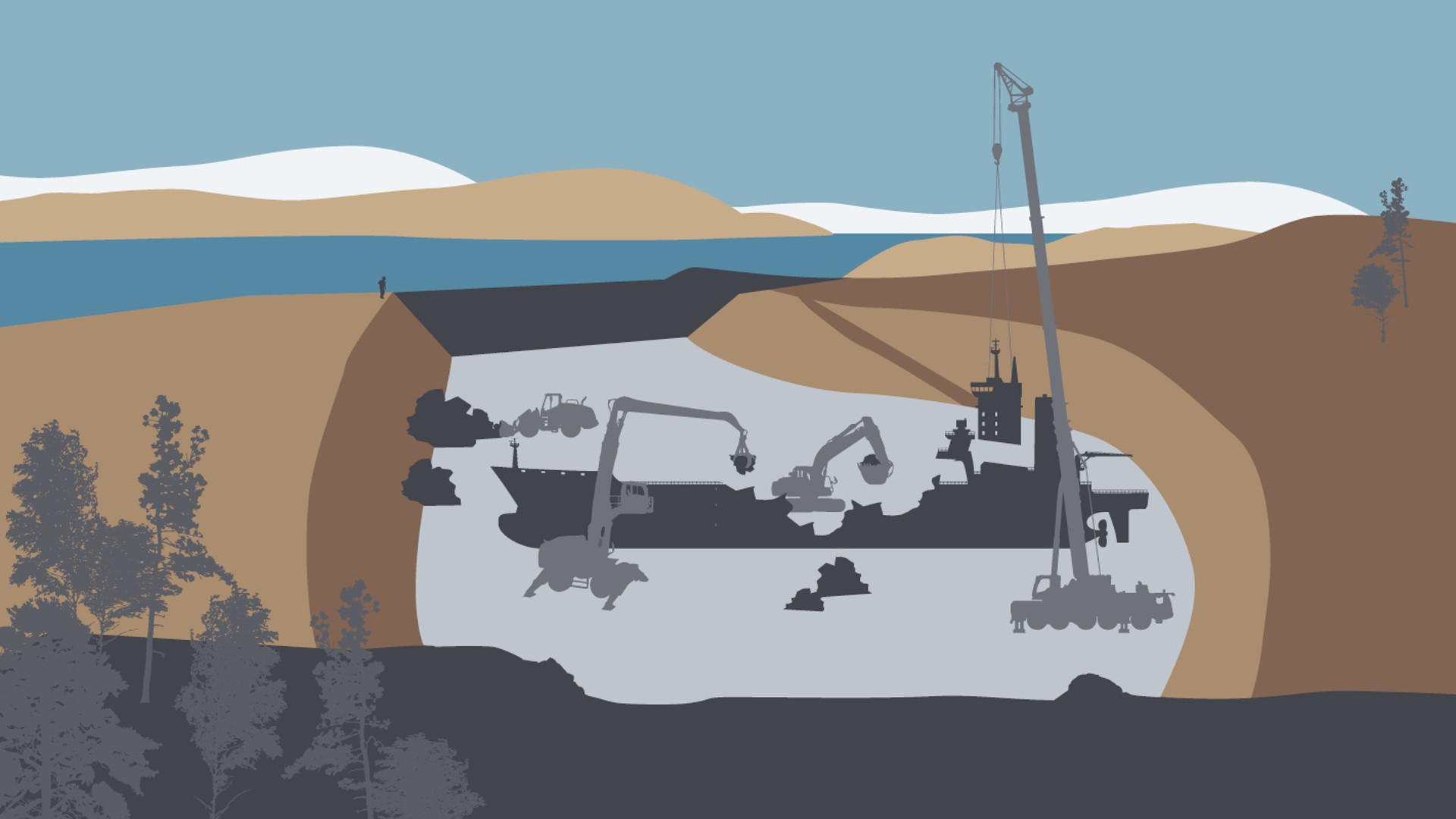

Decommissioning of the MV Kaami at Kishorn Port*

By clicking on “ACCEPT”, you consent to the data transmission to Google for this video pursuant to Art. 6 para. 1 point a GDPR. If you do not want to consent to each YouTube video individually in the future and want to be able to load them without this blocker, you can also select “Always accept YouTube videos” and thus also consent to the respectively associated data transmissions to Google for all other YouTube videos that you will access on our website in the future.

You can withdraw given consents at any time with effect for the future and thus prevent the further transmission of your data by deselecting the respective service under “Miscellaneous services (optional)” in the settings (later also accessible via the “Data protection settings” in the footer of our website).

For further information, please refer to our Data Protection Declaration and the Google Privacy Policy.*Google Ireland Limited, Gordon House, Barrow Street, Dublin 4, Ireland; parent company: Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA** Note: The data transfer to the USA associated with the data transmission to Google takes place on the basis of the European Commission’s adequacy decision of 10 July 2023 (EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework).*The video is embedded from an external source © John Lawrie Group

Ships as a source of recyclable materials

This is why the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) placed the safe and environmentally sound dismantling of ships on its agenda for 2009. The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships has set globally applicable rules for this purpose. For example, each ship must be issued an Inventory of Hazardous Materials drawn up in advance. Ship-breaking yards will in future be required to have a certificate and submit a specific recycling plan for each ship before it is dismantled. But there is a catch: the Hong Kong Convention cannot enter into force until it has been ratified by at least 15 countries, representing more than 40 percent of the world gross tonnage of ships. In 2019, Germany was the 13th state to certify ratification - thus raising the achieved quota to 29.42 percent. So there is still work to be done.

In the meantime, however, the European Union is already implementing some of the rules in the Convention. According to Regulation (EU) No 1257/2013, ships of 500 gross tonnage and more that are flying the flag of an EU member state may only be dismantled at specially authorised recycling yards. The purpose of this regulation is to prevent, reduce, minimise and, where possible, eliminate accidents, injuries and other adverse effects of ship recycling on human health and the environment.

The shipping industry can thus make an important contribution to a circular economy where products or materials can remain in use longer, thus protecting the Earth’s natural resources. For example, life cycle assessments have shown that for every tonne of repurposed steel there is a CO2 equivalent saving of more than 97 percent over new manufactured prime steel products. CO2 equivalents are a unit of measurement that allows us to compare the effect of all greenhouse gases on the climate. This is quite an impressive figure, especially since CO2 pricing and the legal regimentation of ecological footprints in business and trade are continuing to gain momentum worldwide.

A pioneering project for the circular economy

Scrapping the MV Kaami and recycling its materials thus also proved to be a pioneering project in terms of sustainability and the circular economy. A general cargo vessel recovered the wreck and towed it to the dry dock at Kishorn Port, which opened one of its 13,000-tonne gates for the first time for this purpose. The state-of-the-art facilities served as a sort of workshop for the oil boom in the 1970s and was renovated and converted into a gigantic recycling facility after 20 years of inactivity.

Covering an area of 160 metres by 160 metres, the dry dock provides ample space for large freighters such as the MV Kaami and all the cranes, material handling equipment, crawler excavators, wheel loaders, lorries, and other vehicles needed for a meticulously planned and safe dismantling, sorting and removal process – while at the same time complying with all the coronavirus social distancing and hygiene rules required by law.

13 weeks passed from the shipping company’s initial consultation with the recycling company and the operators of Kishorn Port to the delivery of the dismantled and sorted material to the steelworks. The sheer size of the ship should be enough to give you an idea of the scale of the project. The MV Kaami measured 89.8 metres in length and 13.19 metres in width. The material to be processed and transported weighed in at 1,200 tonnes. The demands placed on the workers and materials in the dry dock were correspondingly high. Efficient and safe cooperation between all the parties involved is essential – as are the powerful Liebherr machines that perform reliably even under rough sea conditions. The operation ran smoothly with no safety incidents - thanks to great communication and teamwork.

Robust Liebherr machines designed to meet the toughest requirements are also essential for safe and efficient work in a dry dock.

Working on the rough Scottish seas

But material handling technology was not the only important factor in the decommissioning of the MV Kaami at Kishorn Port. Recycling experts took a very close look at each piece of material and tested its recyclability. The goal was to avoid sending waste to landfills and to recycle as much material as possible.

After the ship had been dismantled, the materials were sorted and separated by the scrapping team. Several Liebherr machines were involved in the decommissioning of the cargo vessel. Two crawler excavators, an R 944 C Litronic and an R 956 Litronic, equipped with scrap shears, dismantled the ship into its individual parts. Two mobile material handling machines were used for loading during the removal process. An LH 40 M Industry Litronic loaded the material onto the lorries waiting in the dry dock below.

At the quay, an LH 50 M Industry Litronic was ready for loading the scrap onto a ship, which then carried it to a steelworks to be melted down and processed into new products. Shipping directly from the site saved on transport by road (approximately 48 articulated vehicle loads) and therefore helped to cut even more carbon emissions.

“The use of the Liebherr machines clearly demonstrated that without modern handling technology, it would not be possible to recycle materials on such a large scale”, explains Andreas Scheuerl, General Manager Sales Materialhandling Equipment at Liebherr-Hydraulikbagger GmbH. This means that the time-consuming and dangerous manual process can be replaced by efficient and economical material handling.

Top performance where it’s most needed

“Handling steel scrap and other metals is one of the toughest fields of operation”, says Scheuerl. The extremely robust construction of the Liebherr material handling machines, designed to meet the toughest requirements, has proven a great advantage in daily use, especially on the rough Scottish Seas. “The sophisticated engine technology and optimised, demand-controlled hydraulics provided maximum performance and efficiency when it came to sorting scrap and loading lorries and ships in the dry dock”, Scheuerl comments.

After 13 weeks, when the dry dock at Kishorn Port was ready to open its gates again and flood the construction site for the next decommissioned ship, the MV Kaami finally became history. But the history of sustainable scrapping is still unfolding, with extremely exciting perspectives for a new form of the circular economy.

A weighty contribution to climate protection

Protecting the climate sometimes requires heavy-duty equipment: Liebherr mobile cranes, material handling machines and earthmoving equipment play a key role in the resource-saving circular economy. They score highly with increasingly environmentally friendly and sustainable, innovative technology.

Heavy equipment used at ship-breaking yards, scrapyards and recycling centres: no matter how hard the work, the environment is always a priority. Our Liebherr developers work across all divisions to ensure this with both large and small innovations – one step at a time, they are making construction and work machines increasingly efficient and environmentally friendly. This not only helps us achieve our climate targets, but also saves the users money and makes our work safer.

Jan Keppler, Head of Product Management for Telescopic Cranes at Liebherr-Werk Ehingen GmbH

Reducing exhaust emissions

“We have been working consistently on making our mobile cranes more environmentally friendly and sustainable for many years. Over the last 20 years, we have been able to steadily reduce exhaust emissions by more than 95 percent, for example. Having successfully adopted the new Stage V emissions limits, we have demonstrably and effectively reduced our nitrogen emissions in daily use, both on the road and on construction sites.

Our soot particle emissions are at the lower threshold of what can be detected by existing measurement technology. The closed particulate filter system removes almost all soot particles from exhaust gas. Soot is therefore no longer to be found at the exhaust tailpipe.

Less is more:

- ECOdrive in drive mode: -5% CO2 and fuel consumption

- ECOmode in crane operation: -10% CO2 and fuel consumption

We have converted our entire crane range to the SingleEngine concept, i.e. we now install only one engine in each crane instead of the former two. This further helps reduce our carbon footprint in production. Improvements in traction drive and crane drive technology, combined with our progress in lightweight construction, have enabled us to substantially reduce the fuel consumption and thus the carbon footprint of our cranes in relation to their lifting capacity.

Today, we are working hard to make our entire fleet HVO-ready. HVO is a synthetically produced fuel that is largely derived from waste materials. And, importantly for us, it is for the most part carbon neutral. Switching to HVO will reduce the CO2 consumption of a 5-axle mobile crane by 74 % if the full ‘cradle to grave’ approach is applied. This is a milestone on the road to low CO2 emissions.”

Love until the final voyage

Ship ahoy! Nicole Langosch, Germany’s first female cruise ship captain, talks to us about the special connection between people and seagoing vessels.

Ms Langosch, what role did your relationships with individual ships play in your nautical journey?

The memory of the first ship you sign on for always has a very special place in your heart. In my case, this was the “Cielo del Canada”, a 2,500 TEU container vessel on which I began my career as an on-board trainee. But the same applies to the ships that I was involved with from the ground up as new builds and that I helped to put into service. And of course the AIDAsol, which I captained.

You literally had to get up close with the container vessel and help out with chipping and painting. How did this change and shape your relationship with the ship?

For one thing, it gives you a feel for the different materials and tools on board a ship. This is about appreciation, but also about taking “responsibility” for the materials and the ship. But the main thing is that by doing basic maintenance tasks, you learn to appreciate the work that you will be responsible for later on as a captain.

You are Germany’s first female cruise ship captain. What does it feel like to see a proud ocean liner embark on its last voyage before being scrapped, as we saw only recently with the MS Astor?

It is always a very emotional moment when a ship sets out on its last voyage and is then “beached” or scrapped. Every ship has its own story to tell. For many crew members, the ship is their “home” for several months or even years. Watching these scrapping videos always makes me very sad. At the same time, however, I realise that it is a highly technical construct. And if all the materials used can be recycled, then that’s a lovely life cycle for a ship whose service life sometimes lasts 25 to 30 years, depending on where it travels and where it is used.

People associate “White Fleet” cruise ships with blue skies and beautiful seascapes. What expectations does this place on a ship’s environmental compatibility – especially after its final voyage?

Climate change has made environmental aspects increasingly important for the cruise sector in particular, but also for shipping in general. High demands are made on the environmental compatibility of the ships being built now and in the future. This is partly to reduce emissions in the future and minimise the ship’s environmental footprint, but also to make it possible to recycle the elements once they have been scrapped.